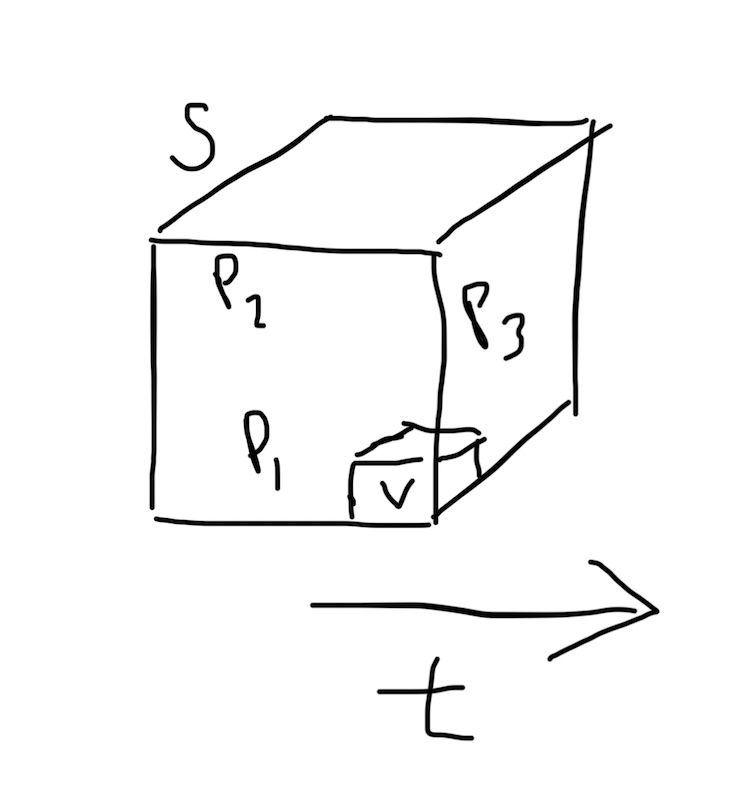

S = side length of box. P = pattern. t = time. V = voxel side length.

March 30, 2024 — Given a box with side S, over a certain timespan t, with minimum voxel resolution V, how many unique concepts C are needed to describe all the patterns (repeated phenomena) P that occur in the box?

As the size of the cube increases, the number of concepts needed increases. An increasing cube size captures more phenomena. You need more concepts for a box containing the earth than for a thimble containing a pebble. As your voxel size--the smallest unit of measurement--decreases, the number of concepts needed increases. As your time horizon increases, the number of concepts needed increases, as patterns combine to produce novel patterns in combinatorial ways, and some patterns only unfold over a certain period of time. Although, past a certain amount of time, maybe everything just repeats again. In fact, it seems likely that the number of concepts C would grow sigmoidally with each of these factors.

Why are there any patterns at all? Why isn't the number of concepts zero? Why doesn't every box just contain randomness? There could be ~infinite random universes, but this one, for sure, contains patterns.

What is a pattern? A pattern is something accurately simulatable by a function. A concept really is just a function that simulates something, with inputs and outputs. A concept could be embodied in different ways: by software, by an analog computer, by an integrated circuit, by neurons, et cetera. If all you had in your box was a rock, you could have a concept of "persistence", which is that a rock is persistent in that it will still be there even as you increase the time.

Brains are pattern simulators, and symbols are a way for these simulators to communicate simulations.

You can classify patterns into natural patterns and man-made patterns. Mitosis is a natural pattern. Wheels are a simple man-made pattern and cars are a man-made pattern made up of many, many man-made patterns.

Science is the process of discovering patterns, mostly natural, and tagging them with concepts.

It's fairly easy to tag new man-made patterns with concepts. There are max eight billion agents generating these (in practice, much less), and we can tag them as we create them.

But by the time we arrived on the scene with our tagging abilities, nature had already developed a backlog of a mind-numbingly large number of untagged patterns.

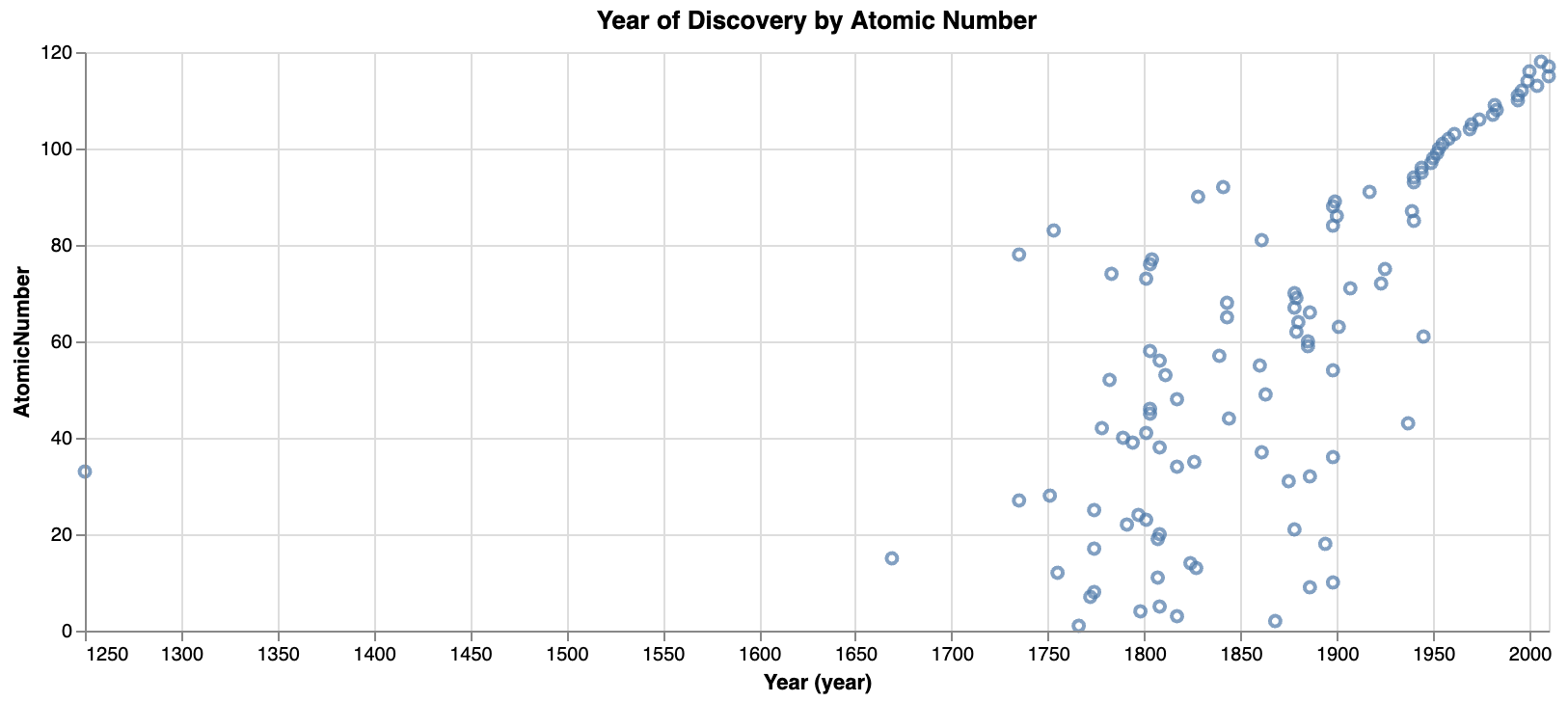

The box at the element size is well described. Scientists have identified all the natural elements and the only new ones are man-made.

Scientists had a lot of low hanging fruit patterns to tag.

If you put a box around the earth, what percentage of nature's patterns have been tagged? Are we 50% done? Are we 1% done? Are we 0.0001% of the way there? Are we something like 45% of the way there, with greatly diminishing returns, approaching some hard limit of knowability? Or will be there a point where we've successfully uncovered all the useful patterns here on earth?

Both nature and man are constantly creating new patterns combinatorically. How many new microbes does nature invent everyday? Who is inventing more patterns nowadays on earth: nature or man? How has that race changed over time? What about if you extend your box to contain the whole universe?

If you put a box around our universe, what were the first patterns in it? How is it that a box can contain patterns that evolve to be able to simulate the very box they are in?

A decreasing voxel size allows for identifying concepts that can generate predictions impossible with a higher voxel size, but also increases the number of untagged patterns.

Something being unpredictable after much effort means it is either truly unpredictable or just that the true pattern has not been found yet. That might be because the box is too small; the box is misplaced; the voxels are too big; the needed measurements cannot be taken; the measurements are not being taken enough over time. It does seem like the process of finding the right formula is not so hard, once the right data has been collected.

We often have a lot of Misconcepts. A concept that doesn't really explain a pattern. Maybe it is correlated with some parts of a pattern, but it is very lacking compared to some concepts that are far more reliable. You could also call these bullshit concepts.

If you put a box around a bunch of bricks, we seem to have a pretty good handle on all the useful concepts. Put it around a human brain though, and we still have a long way to go. Though, if you think about the progress made in the last 50 years, you can imagine we might possibly get far further in the next 50, if diminishing returns aren't too strong.

Can we make empirical claims about how many concepts C can we expect to describe patterns P given a box of size S, voxel size V, over time T? Perhaps it is possible to use Wikipedia to do such a thing. Maybe if you plotted that we would see the general relationship between these things.

Why might answering this question be useful? If we consider an encyclopedia E to contain all the useful concepts C in a box, then we might be able to make predictions about how complete our understanding of a topic is, regardless of the domain, by taking simple measurements of E alongside S, V, and T.

Sorry if you were expecting some quantified answers, as I haven't done that hard thinking, yet. This post is early explorations of trying to think of what science is from first principles. Scientists and engineers and craftsmen have done absolutely amazing things in so many fields, but I'm very interested in an area where science has so far failed, and I try to think of possible root causes of that failure. In those situations, it might just be a matter of time (waiting for technologies to decrease voxel size, or take previously impossible measurements).

If you are interested in the concept of the evolution of patterns in nature, I recommend checking out assembly theory.